Plea Deals, But No Mercy

Plea bargains are a main staple of the criminal justice system, yet the public knows little or nothing of what they entail. According to Los Angeles District Attorney Steve Cooley, ninety-six percent of California’s criminal cases end by plea bargains, which is about the national average.

Plea bargains are the pressure valve for overburdened court systems where a never-ending line of criminal trials can endure for as little as a few days or drag on for years at a time. These courtroom deals, as they’re sometimes called, relieve stressed public defenders’ offices, save taxpayers millions of dollars by circumventing costly trials where lawyers and investigators charge hundreds of dollars by the hou8r, and relieve civilians of time-consuming jury duty.

For the accused, plea bargains save people from the experience of humiliating and invasive public trials; from the expense of financially draining defense counsel, and sometimes, they reduce probable harsher sentences that could potentially follow a jury conviction.

A plea bargain is a formal agreement with the government—a contract, if you will—for a guaranteed and specified outcome. A plea bargain is supposed to be a win-win situation. However, as the story of Eric Davis illustrates, win-wins are not always the case.

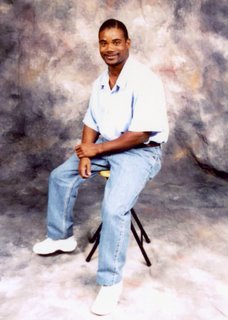

Davis, a California three-striker, suffers from a sixty-year sentence for, as many call it, an ancient history of robberies. On its face it might seem just that a repeat offender got what he deserved. Yet, as with most legalese, it’s much more complicated than that.

Davis, a fifty-six year old father of two, committed his first robbery at age nineteen—in 1968—twenty-six years before the enactment of the Three Strikes Law.

After his release from the ’68 robbery, Davis went straight, adopting a career in upholstery, while practicing music on the side./ Some eight years later, having fallen on hard times, he reverted back to robbery. Following a four year prison stint, from 1976 to 1980, he was released and managed to keep himself clean for fifteen years, until he was arrested in 1995 for the third time for another robbery (with mitigating circumstances because he used no gun during the crime).

Davis now sits warehoused in prison, expected to languish for more than twice the time a person would get for two homicides. Imagine, a sentence of six decades in prison for three completely isolated incidents, albeit, criminal, in which no one was ever injured. His offenses spanned some thirty-seven years, two of which occurred before the Three Strikes law was even a concept.

Davis readily acknowledges that criminal behavior shouldn’t be overlooked simply because he fell on hard times. Indeed, millions of people are subjected to hard times and don’t revert to criminal behavior. Still, the fact that the government would go back decades to strike a person out for life is wholly unfair and unjust.

According to Davis, his first offense was supposed to be sponged from his record when he turned twenty-one; after he met all the conditions of his parole term. Normally, that would have been the end of the case. Had that conviction been stricken, according to the plea agreement, the maximum sentence for his current offense would have been fourteen years; still a stretch to any observer who values human life.

Davis considers himself a victim of the state by deception. He, like scores of others, took plea agreements that saved the state time, inconvenience and money in exchange for what should have been settled and closed agreements, only to have the state renege and arbitrarily hold those plea agreements against them decades later. For the objective onlooker, giving people strikes for settled cases, years after the fact, is a gross breach of contract.

In legal terms, this constitutionally offensive practice is referred to as ex post facto, which in Latin literally means “after the fact.” The Three Strikes Law makes past criminal convictions, for which were already paid, eternally greater after the deal—with no warning of possible changes or future application; a complete departure from the original agreement.

Normally, ex post facto laws prohibit the retroactive application of new laws to past offenses.

Using a rather conspicuous but current case is that of Dennis L. Rader and how the retroactive application of the death penalty was prohibited in his circumstances. The fifty-nine year old Kansas man tortured and murdered ten men, women, and children from 1974 to 1991. Many people assumed Rader, definitely one of the worst of the worst, would be eligible for the death penalty. However, Kansas hadn’t enacted the death penalty until after Rader’s infamous killing spree had quietly subsided. Keeping within the framework of ex post facto, Kansas officials announced that Rader was ineligible for death after he was finally arrested in 2005. The harshest sentence he could receive was one hundred seventy-five years.

In the 1970 case of Santabello v. New York, the court explains the injustice of violating ex post facto and almost prophetically describes what later came to be California’s Three Strikes Law: “By retroactively increasing terms to be imposed for enhancement purposes, the state has changed a factor of consideration to the detriment of the [contractee]. This is fundamentally unfair; which could result in a doubling of a sentence, or even life imprisonment for future offenses. Without foreknowledge of this [shift] in liability petitioner’s plea agreement was neither voluntary or knowing.”

Unfortunately, the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in the case of In re Andrade and Ewing v. California in 2003 drastically strayed from these protections and allowed California’s practice of violating ex post facto to stand, retroactively striking out thousands of California citizens accused of crimes. Reprehensibly, the majority of those struck out constitute African Americans. While African Americans make up just seven percent of California’s overall population, they represent forty-seven percent of the three-striker population.

It remains to be seen how this turnaround could affect other laws, perhaps arbitrarily affecting the work place, civil cases and other aspects of American daily living.

When I asked Davis how he felt about the Supreme Court’s departure from the common interpretation of ex post facto he said, “I hope that people will wake up and realize that when it comes to stripping down civil and other protections, the wide gap between even the rich and the poor grows a lot closer.”

Sources:

Eric Davis, CDCR# K-4206

Erica Warner, “Report: States 3-Strikes Law Needs to be Changed,” AVP, September 23, 2005: All; Families to Amend Three Strikes, facts1.com, (the law affects minorities disproportionately).

Steven H. Gifis, Barron’s Law Dictionary, Third Edition, (Barron’s Educational Series, Inc., New York, NY, 1991): p. 176.

Patrick O’Driscoll, “Witcha Cheers Arrest of BTK Killings,” USA Today, February 28, 2005: 3A (Re: Dennis L. Rader arrest).

David Savage and Henry Weinstein, “Justice Finds California’s Sentencing Law Flawed,” Los Angeles Times, January 23, 2007.